Doubt and Darkness

When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, reasoned like a child . . . and the questions of faith and life that plague us all were most often put to rest by the confident creeds and dogmas of parents and a religious tradition rich in doctrine. And if I’m honest, I will admit that the certainties of faith and belief that shaped my early years still are formative in ways I don’t always understand. Perhaps most of us can admit to the comfort and confidence of well-defined childhood faith.

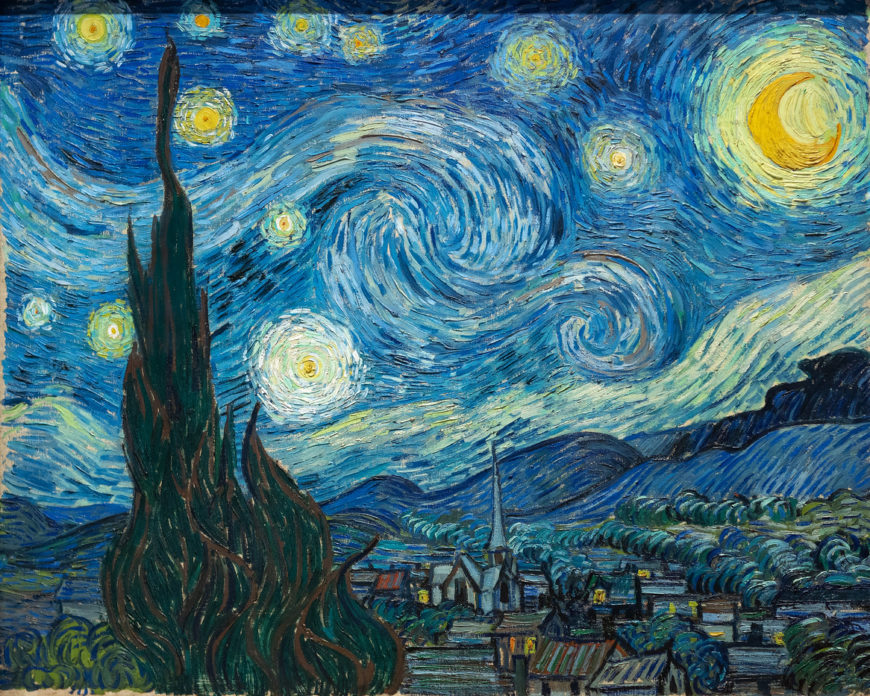

But being curious and strong-willed and no doubt more than a little full of myself, it wasn’t long until even a child rather smitten with religious ideas and issues began to challenge and question. Those summer forays exploring the islands around us and the depths below our leaky small skiff or the dark nights outside sleeping under the stars all played a part in the gathering momentum of doubt and questions. Together with age and ever-expanding experience, they both affirmed the wonder of the universe and confirmed a certain bewilderment about the complexities of the multifaceted, complicated world we call home.

Doubt and fear of the unknown are familiar companions. Most of us can recall childhood fears of the dark and the ever-present doubts that nip at our heels and speak in the interminable voices playing relentlessly in our heads. We all know the weight of the world in the dark hours of the night when problems of life seem insurmountable and where there is no going back to the seeming simplicity of childhood. When the markers of certainty, those creeds we once professed with such confidence, no longer work or when despair or hopelessness plunge us into darkness, then what? Can living with doubt and embracing darkness be redemptive, life-giving? A benediction?

John of the Cross, a sixteenth-century Carmelite monk, wrote from his prison cell in Spain (a place his order hoped would silence him), that the dark night of the soul is God’s best gift. By this, John of the Cross did not mean that agony or angst are to be venerated. He was not glorifying suffering, nor did he mean, as has been sometimes attributed to him, that doubt and darkness are places of fear or despair. John of the Cross experienced liberation in the darkness of his prison cell. He found there freedom from our attachment to the doctrines, beliefs, and creeds that we think will leave us feeling secure and closer to God. He found freedom from all the ways we try to define God—freedom in uncertainty. In the darkness of his exile, he learned to trust God in the absence of certainty about God.

As in all of human history, we live in uncertain times. The world is small, and we know its fragile state all too well. Fear is rampant today. It drives our society into a frenzy of traps we hope will bring us longed-for security and iron-clad safety. For many, our facile attempts to find answers or solutions in religion no longer work. The God we may once have defined as the way, the truth, the life is understood differently in other traditions and cultures and the creeds we once confessed with such lock-step assurance often feel outdated or strangely anachronistic. There seems to be no permanently safe place to settle.

But might it be that in the midst of our angst, in the places where we all hang on for dear life, new birth can take place? The darkness of the night becomes the birthplace for a new day. Perhaps the certainties of childhood or even adulthood were not so much about defining an indefinable God as they were about a system of beliefs that no longer works. If we are honest, we’ve known all along that God cannot be grasped or contained in words or pictures or doctrines. If we are honest, we know that all our feeble attempts to explain the sacred mystery of things are just that, woefully inadequate stabs at containing what cannot be contained.

With John of the Cross, I want to learn to trust God in the absence of certainty about God. I want to know the liberation he found in the darkness of his prison cell—freedom in uncertainty. Most of the time, that is enough. God’s presence and what feels like God’s absence can exist together. There are no precisely right words and no one tradition that nails it all down. I can live with that as a benediction. In the silence of a dark night and surrounded by a chaotic world that seems out of control, the undefinable mystery of God and God’s holy presence is enough. That is benediction indeed.

REFLECTION

He found freedom from all the ways we try to define God—freedom in uncertainty. In the darkness of his exile, he learned to trust God in the absence of certainty about God.

- What does it mean that John of the Cross experienced liberation in the darkness of his prison cell?

- How do you understand doubt? Darkness?

- Does it make sense to you that God’s presence and God’s absence can exist together?

- How might doubt and darkness convey freedom?

- Is the undefinable mystery of God enough?

Taken from Benedictions: 26 Reflections. Copyright © 2016 Julie K. Aageson. All rights reserved. Used with permission of the author.